Across the Tundra: A Painting’s Journey & Stories of Community

〰️Bridging Generations Through Paint, Story, and Place〰️

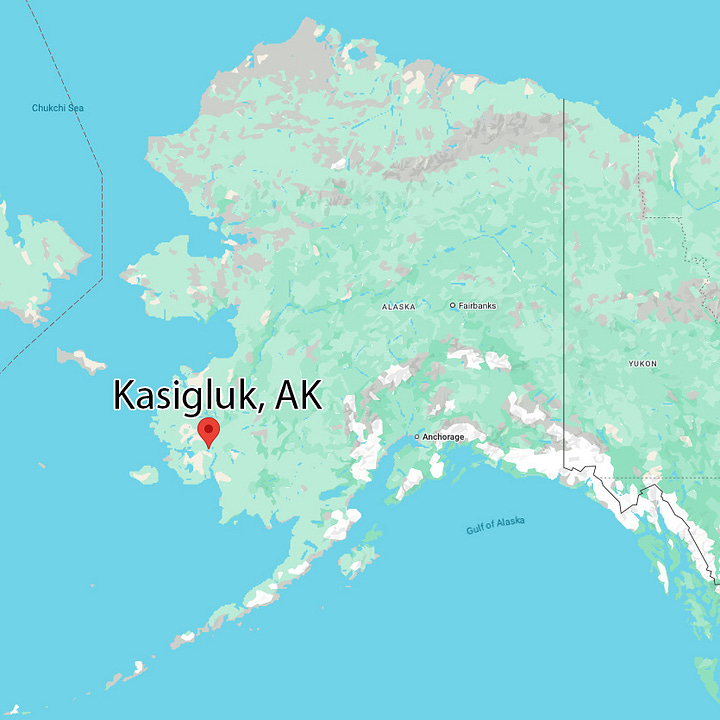

Large painted canvases, carefully wrapped and secured, boarded a small bush plane in the village of Kasigluk, Alaska. Its destination: Bethel, the hub city on the Kuskokwim River that connects 56 Yup'ik villages spread across the tundra. The painting—created by young hands guided by elder stories—was to serve as the backdrop for a performance that bridged generations.

But before that, there was the journey just to begin.

Bethel, AK sits at the heart of a region where traditional Yup'ik practices, language, and subsistence ways remain deeply rooted despite profound changes. Alaska became a state relatively recently (1959), and holding onto ancestral traditions in the face of a new government has been complex, to say the least.

“Now we must be of two minds.”

Those who lived through this change—mandatory U.S. schooling, punishment for speaking one's native language, and imposed restrictions that made subsistence ways untenable—are grandparents now. Shouldering the traumas they experienced, many resiliently worked together to bring about shifts that are present today, such as Yup'ik immersion schools like the one in Kasigluk, to retain and revitalize their culture. The youth, however, do not have firsthand experience of pre-statehood, nor did they witness how hard their elders worked to preserve their culture. In a world that continues to shift around them, how do young people connect to these deep traditions, and how are stories passed down? Story, which Yup'ik culture has always relied on to preserve history, traditions, and values, remains one active way families and communities bridge generational understanding.1

This history brought us to this moment—a chance to reflect on the past, be present, and stay connected to the future. From choosing the colors of paint to figuring out how to get everything out there—across frozen rivers and through stormy skies—each step was part of the journey, and in a way, it was its own story.

Getting art materials to the village was its own act of coordination and care. From Anchorage to Bethel, then on a bush plane to the Akula side of Kasigluk, supplies were finally loaded onto snow machines and driven across the frozen Johnson River to Akiuk School. Boxes of canvas, jars of paint, brushes, tape, and tarps arrived bundled with possibility—each item a quiet invitation to translate memory into form.

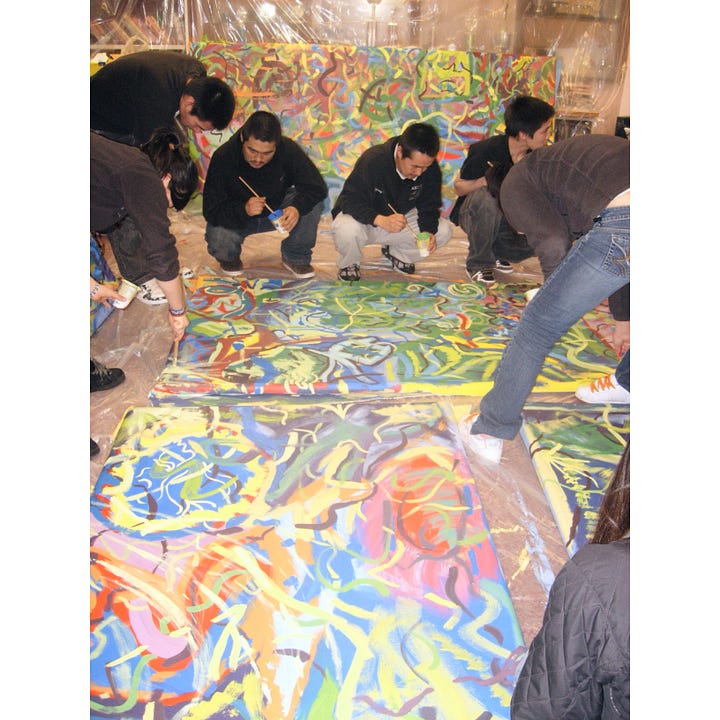

Inside Akiuk School, the library became the makeshift studio. It was February—light was scarce, the temperature dropped to -40°F, and a blizzard swept through. Even then, school only had a late start. Life continued, as it does here. Tarps covered the floors, creating space for everyone to participate—students, teachers, elders, and parents. Together, they worked in this shared space, where the walls soon filled with color, shape, and stories. Each decision—what marks to make, where to layer, when to leave space—became part of the process. As youth and elders worked side by side, visual language emerged: non-linear, layered, and sometimes uncertain, but full of care. The paintings carried the textures of process as much as product: brushstrokes in conversation with story, geometry intersecting with memory.

In Kasigluk, the community’s deep connection to one another led to what happened next. All I had to do was set the scene. The answer looked like shared tables, full walls, big questions, and quiet acts of trust between generations. The paintings are evidence of that process—a visual record of what it means to belong to a story larger than yourself.

The finished paintings traveled to Bethel to serve as the visual foundation of YUPIULLEQ NUTEM, a performance event involving over 100 participants from across the region. Before a single word was spoken, the canvases filled the space—anchoring the room with story. These weren’t just set pieces; they were containers of shared experience, created by the youth but echoing the lives and legacies of their elders. The performance included drumming, interviews, song, and dancing. People gathered from surrounding villages, dressed in their best kuspuks, as the stories told in the paintings came to life through music and movement.

After the performance, the canvas made the return journey home to hang permanently in the village school, where community life unfolds daily. This circular journey of art echoes the deeper cycles of cultural knowledge being passed between generations in southwest Alaska.

The paintings now hanging in Kasigluk's school continue their work silently. Students pass them daily, community members gather beneath them for meetings and celebrations, and the stories they contain continue to speak—asking questions, offering comfort, and reminding everyone who sees them that art can be more than just something beautiful to look at. It can be a bridge between what was, what is, and what might yet be.

𝗧𝗲𝗮𝗰𝗵𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗮𝗿𝘁𝗶𝘀𝘁 𝘁𝗲𝗮𝗺:

Director/Lead Interviewer: Ryan Conarro

Traditional Dance/Drumming: Qacung Blanchett (Yup’ik)

Traditional Dance/Drumming: Gary Upay’aq Beaver (Yup’ik)

Visual Lead: Sarah Conarro

Music: Patrick Murphy

Culture-bearer and teaching artist: Nita Rearden (Yup’ik)

Producer: Bev Williams + Julie McWilliams

Commissioned by the Lower Kuskokwim School District Pilinguat Project.

Presented at the Orutsararmiut Native Council Hall, Bethel, Alaska, 2011.